When the FBI originally released the “final” crime data for 2022 in September 2023, it reported that the nation’s violent crime rate fell by 2.1%. This quickly became, and remains, a Democratic Party talking point to counter Donald Trump’s claims of soaring crime.

But the FBI has quietly revised those numbers, releasing new data that shows violent crime increased in 2022 by 4.5%. The new data includes thousands more murders, rapes, robberies, and aggravated assaults.

The Bureau—which has been at the center of partisan storms—made no mention of these revisions in its September 2024 press release.

RCI discovered the change through a cryptic reference on the FBI website that states: “The 2022 violent crime rate has been updated for inclusion in CIUS, 2023.” But there is no mention that the numbers increased. One only sees the change by downloading the FBI’s new crime data and comparing it to the file released last year.

After the FBI released its new crime data in September, a USA Today headline read: “Violent crime dropped for third straight year in 2023, including murder and rape.”

It’s been over three weeks since the FBI released the revised data. The Bureau’s lack of acknowledgment or explanation about the significant change concerns researchers.

“I have checked the data on total violent crime from 2004 to 2022,” Carl Moody, a professor at the College of William & Mary who specializes in studying crime, told RealClearInvestigations. “There were no revisions from 2004 to 2015, and from 2016 to 2020, there were small changes of less than one percentage point. The huge changes in 2021 and 2022, especially without an explanation, make it difficult to trust the FBI data.”

“It is up to the FBI to explain what they have done, and they haven’t explained these large changes,” Dr. Thomas Marvell, the president of Justec Research, a criminal justice statistical research organization, told RCI.

The FBI did not respond to RCI’s repeated requests for comment.

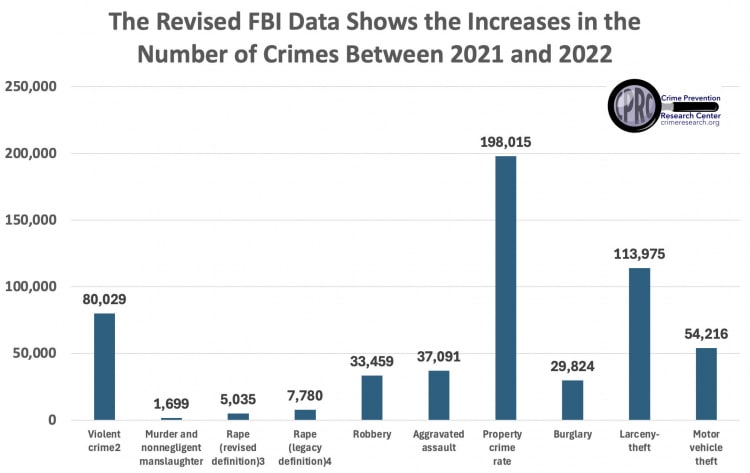

Extensive revisions in violent crime stats

The actual changes in crimes are extensive. The updated data for 2022 report that there were 80,029 more violent crimes than in 2021. There were an additional 1,699 murders, 7,780 rapes, 33,459 robberies, and 37,091 aggravated assaults. The question naturally arises: should the FBI’s 2023 numbers be believed?

Without the increase, the drop in violent crime in 2023 would have been less than half as large—only 1.6% instead of the reported drop of 3.5%.

The FBI isn’t the only government agency that has been revising its data. The Bureau of Labor Statistics massively overestimated the number of jobs created during the year that ended in March by 818,000 people.

The FBI’s crime stats revisions reveal how much guesswork is involved in even the “final” numbers often seized on by politicians. The FBI doesn’t simply count reported crimes. Instead, it offers estimates by extrapolating data from police departments that report only partial-year data. The Bureau also makes estimates for cities that report no data. The FBI’s method of generating these estimates changes over time, and it affects the figures they report.

“The [FBI’s] processes, such as how it tries to ‘estimate’ unreported figures, has long been a black box, even to the Bureau of Justice Statistics—the Department of Justice’s actual statistical agency,” says Jeffrey Anderson, who headed the DOJ’s Bureau of Justice Statistics from 2017 to 2021.

Anderson said when he headed the Bureau of Justice Statistics, “We definitely would have highlighted in a press release or a report the 6.6% change recorded for 2022, which moved the numbers from a drop to a rise in violent crime.”

Many crimes are unreported

Another problem with FBI crime data is its reliance on reported crimes. Most crimes go unreported, with only about 45% of violent crimes and 30% of property crimes brought to the police’s attention, according to the National Crime Victimization Survey. Since the FBI only tracks reported incidents and this gap is so large, researchers argue that when the media discusses crime rates based on FBI data, they should clarify that it reflects “reported” crime, not give the impression that total crime is changing.

Nonreporting of crime doesn’t affect all crimes equally. Nonreporting of murder and motor vehicle theft is relatively rare. In murder cases, victims can’t be overlooked, and for auto theft, insurance claims require police reports. However, it’s difficult to fully trust even these numbers because the FBI underreported 1,699 murders and 54,216 motor vehicle thefts in 2022, casting doubt on the reliability of the data.

Although recent attention has focused on the decline in murder rates, even with the revised numbers, the 16.2% drop from 2020 to 2023 still leaves murder rates 9.6% higher than pre-COVID levels.

A half-century ago, the DOJ provided a total crime measure, including both reported and unreported crime. The results of the department’s Bureau of Justice Statistics 2023 National Crime Victimization Survey, released in mid-September, tell a very different story from the FBI data.

The NCVS interviews 240,000 people each year about their personal experiences.

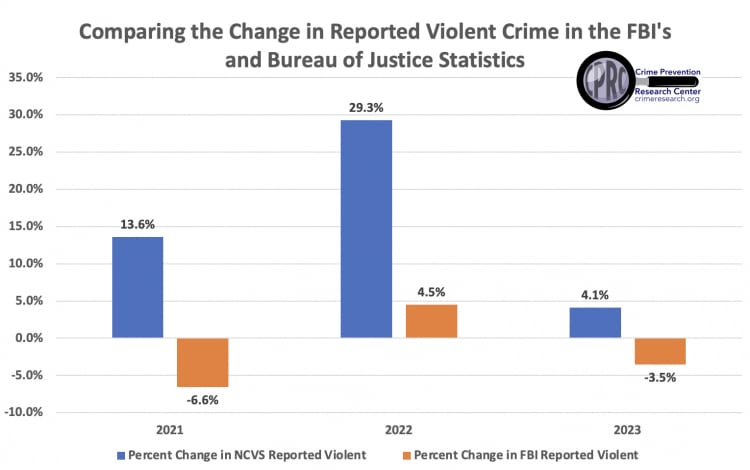

Instead of the FBI’s 3.5% drop in the reported violent crime rate in 2023, the NCVS found a 4.1% increase in the reported violent crime rate. Even with the revised FBI numbers, in 2022, the FBI’s 4.5% increase pales in comparison to the NCVS’s 29.1% increase.

Over the past few years, the number of police officers has declined because of cuts in budgets and many retirements. One result is that police departments nationwide—from Charlottesville and Henrico County, Va., to Chicago, Ill. and Olympia, Wash.—are no longer responding to calls unless the perpetrator is still there actively committing the crime. Instead of police coming out to investigate and take a report, residents in those jurisdictions can still go to the police station and wait in line to get a police report filled out. In addition, despite the widespread belief that calling 911 is enough to report a crime, the FBI officially doesn’t tally 911 calls. It only counts crimes when police make out an official report.

Other data show sharper rises in crime

While the FBI claims that serious violent crime has fallen by 5.8% since Biden took office, the NCVS numbers show that total violent crime has risen by 55.4%. Rapes are up by 42%, robbery by 63%, and aggravated assault by 55% during Biden’s term. Since the NCVS started, the largest previous increase over three years was 27% in 2006, so the increase under Biden was slightly more than twice as large.

The increases shown by the NCVS during the Biden-Harris administration are by far the largest percentage increases over any three years, slightly more than doubling the previous record.

Comparing 2023 rates with 2019 pre-COVID violent crime rates, the FBI’s new 2023 data show virtually no improvement—just a 0.2% drop—while the NCVS shows a 19% increase over that period. But the news media didn’t cover the crime survey when it was released last month.

“With the media using the 2022 FBI data to tell us for a year that crime was falling, it is disappointing that there are no news articles correcting that misimpression,” Moody told RCI. “We will have to see whether the FBI later also revises the 2023 numbers.”

At the beginning of this year, the media was running headlines like National Public Radio’s: “Violent crime is dropping fast in the U.S.—even if Americans don’t believe it.” “At some point in 2022 … there was just a tipping point where violence started to fall and it just continued to fall,” NPR claimed. But now the FBI has itself admitted its violent crime numbers were way off.

Even as polls show that Americans are concerned about crime, the FBI and the media are making it difficult to see how crime rates have changed over the last few years. A Gallup survey late last year found that 92% of Republicans and 58% of Democrats thought crime was increasing. A February Rasmussen Reports survey found that, by a 4.7-to-1 margin, likely voters say violent crime in the U.S. is getting worse (61%), not better (13%). A Gallup poll found in March that “crime and violence” was Americans’ second biggest concern, after inflation. But the media and politicians used the inaccurate FBI data to try to convince people that they were wrong.

“This FBI report is stunning because it now doesn’t state that violent crime in 2022 was much higher than it had previously reported, nor does it explain why the new rate is so much higher, and it issued no press release about this large revision,” said David Mustard, the Josiah Meigs Distinguished Professor at the University of Georgia who researches extensively on crime. “This lack of transparency harms the FBI’s credibility.”

John R. Lott Jr. is president of the Crime Prevention Research Center and he lives in Missoula. He served as senior adviser for research and statistics in the Office of Justice Programs and the Office of Legal Policy at the Justice Department.

This article was originally published by RealClearInvestigations and made available via RealClearWire.

John R. Lott Jr.

John R. Lott Jr. is a contributor to RealClearInvestigations, focusing on voting and gun rights. His articles have appeared in publications such as the Wall Street Journal, New York Times, Los Angeles Times, New York Post, USA Today, and Chicago Tribune. Lott is an economist who has held research and/or teaching positions at the University of Chicago, Yale University, Stanford, UCLA, Wharton, and Rice.