(Center of the American Experiment) — Family Child Care or home-based childcare provides an important lifeline to Minnesota parents who can’t afford center-based care. Unlike centers, family childcare providers are also usually small, have flexible hours, and are more culturally responsive. So, they provide much-needed diversity in the childcare industry.

Unfortunately, under the notion of modernization, the Department of Human Services (DHS) is proposing licensing standards that will likely run family childcare providers out of business. This will raise costs for parents and make it hard for them to find childcare. The results will be especially acute for parents in Greater Minnesota who often rely on family childcare providers.

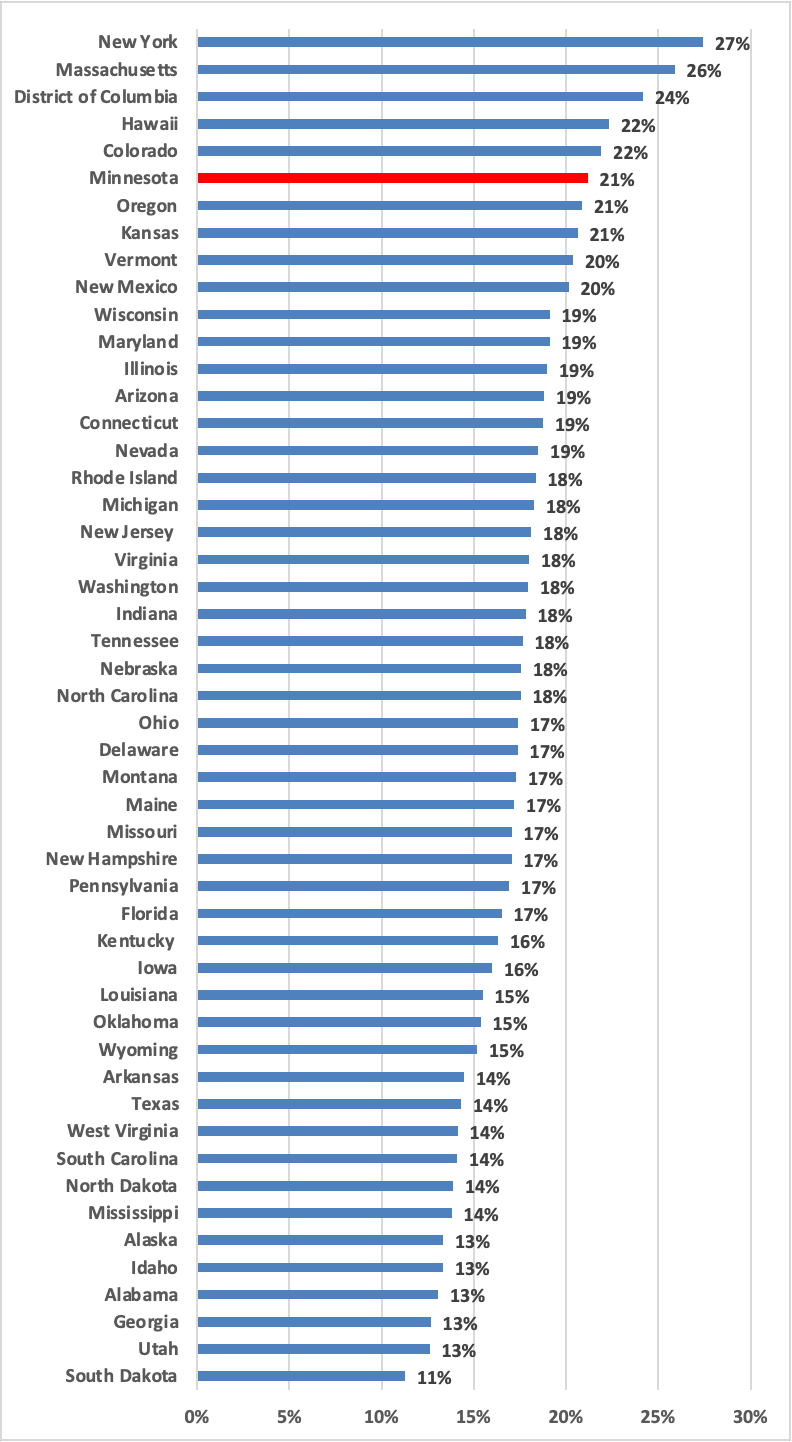

According to ChildCare Aware, in 2022, a household with a median income in Minnesota spent 21 percent of their income to send their infant to a daycare center, making Minnesota the sixth most expensive state for center-based infant care (California not included). For married couple households, that figure was slightly lower at about 14 percent. Still, Minnesota ranked tenth most expensive state for center-based infant care. For a single-parent household, infant center-based care in 2022 took nearly half of all income.

Figure 1: Cost of center-based infant care as a percent of median household income, 2022

Family childcare, on the other hand, was significantly more affordable. In 2022, a household with a median income spent 11 percent of their income to send their infant to home-based childcare. Minnesota ranked as the seventh most affordable state for home-based infant care (California not included). For married couple families the proportion of income spent on family childcare was even lower at 7 percent, making Minnesota the eighth most affordable state. Single-parent households also spent only half as much on home-based infant care as they did on center-based infant care — 23 percent of income.

According to the latest data from ChildCare Aware, while center-based infant care costs nearly $400 per week in Minnesota (nearly $1,600 a month), family childcare providers cost roughly half that.

Figure 2: Estimated weekly average cost of childcare in Minnesota

Sadly, this affordable option might be going away. Here is why.

What the DHS is proposing

From dictating the number of toys, to how often providers should clean their fridges, the DHS is leaving little, if any, breathing room in how family childcare should conduct their business.

Here is a look at some of the proposed new rules

Cleaning rules

Previously Minnesota statute only stated that childcare providers must keep their homes clean. New proposed rules, however, dictate what cleaning products can and cannot be used, how cleaning should be done, and how often such cleaning should be done.

For instance,

(1) Food preparation areas, tables and chairs, high chairs, and food service counters, must be cleaned and sanitized before and after each meal and snack with single use paper towels, onetime use wiping cloths, or microfiber cloths;

(2) Eating utensils, bottles, drinking equipment, and dishes, must be cleaned and sanitized prior to next use. If a parent is bringing a bottle from home, the bottle does not need to be cleaned by the license holder upon arrival;……

(5) Refrigerators must be cleaned and sanitized monthly or more often as needed;

(6) Freezers must be cleaned and sanitized quarterly or more often as needed;

Similar cleaning directions are in place for toys, bedding, toileting areas, furniture, machine-washable clothes, floors, and rugs. Certain sanitizers and certain materials, like aerosols, can’t be used by providers.

Toys and equipment

Previously, outside of an infant chair, and sleeping materials, in-home childcare providers were only required to provide enough age-appropriate materials for children.

With the new standards, however, that has changed. If passed, providers have been given an itemized list of what toys and materials they need for each child. For infants, for example, in addition to a chair, and a sleeping bed or bag, providers must have the following:

(c) Blocks and dramatic play equipment including, but not limited to:

(1) Blocks of various sizes;

(2) Soft dolls to grasp and squeeze;

(3) Soft washable animals;

(4) Play telephone;

(5) Non-breakable mirror located at eye level for crawling infants;

(6) Various pots and pans; and

(7) Play materials that represent a diversity of cultural and ethnic groups.(d) Books and literacy materials, including, but not limited to:

(1) Board, cloth, or plastic books;

(2) Simple story books with one picture per page;

(3) Activity books; and

(4) Pictures and books that reflect the different cultures and background of children and families served by the program.(e) Gross motor activity equipment and areas, including but not limited to:

(1) Small push and pull toys;

(2) Riding toys;

(3) Balls;

(4) Use of equipment such as bouncers or swings limited to less than 30 minutes per day; and

(5) Safe, open space in the room to encourage movement; extending arms and legs, sitting,rolling, crawling, and walking with supports.(f) Fine motor activity materials, including but not limited to:

(1) Rattles with different noises, shapes, colors, and textures;

(2) Easy fit together toys, such as large building block toy sets;

(3) Hanging items for infants to grasp or bat;

(4) Pop-up or activity boxes;

(5) Teething toys; and

(6) Soft toys to grasp.

Similarly, for toddlers, preschoolers, and school-age children, providers must have certain types of toys and equipment. In addition to specifying the type of equipment, proposed laws specify the amount of toys for some ages.

Temperature and looking after infants

While previously, providers had to keep their homes at a minimum temperature of 62 degrees, new rules require a temperature range between 68 degrees and 82 degrees.

Providers must check on sleeping infants after every 15 minutes, down from 30.

Paperwork and documentation

Providers will have to document more things now, including, but not exclusive to, using pesticides. Specifically, providers must notify parents what pesticides will be used and where they will be applied.

Overall, the list of things providers must have documented show to parents, as well as the DHS Commissioner, has grown from 16 to over 25. Going forward, for example, providers must have a written behavior guidance and discipline policy on hand. Other new additions include:

a written policy on screen time that includes caregiver education and screen time use.

situations that may require disenrollment of a child, if applicable, including termination and expulsion notice procedures.

A policy on parental access to the program that states an enrolled child’s parent must be allowed access to the parent’s child inside the program at any time while the child is in care

New environmental rules

A new environmental section has also been added whereby providers must:

- Cover any bare soil to protect kids from lead

- Test water for contaminants

- Use a water filter or provide bottled water if water is not tested.

- Complete radon testing before initial licensure and once every 5 years or once every two calendar years if a radon mitigation system is installed

- Notify the DHS Commissioner when their facility was first built

Likely impact: shortages and higher costs

Minnesota is one of the most expensive states for center-based care. Family childcare providers, therefore, provide a more affordable option to Minnesota families.

Not only are family childcare providers an important source of affordable care, but in greater Minnesota, they are usually the only option. Due to their high cost of operations, centers need dense populations and high incomes to be sustainable. Greater Minnesota, however, has sparse populations and lower incomes, making centers much less financially feasible. So compared to the Metro region, greater Minnesota is especially more reliant on family childcare providers.

Whether new rules will improve safety or quality, as the DHS claims, is a questionable stance. What’s likely to happen, however, is that providers will spend a lot of time and money to comply with the proposed rules. Providers will either have to raise costs for parents or go out of business. The effects of these new rules will be especially acute in Greater Minnesota.

But even for those that stay, chances are a lot of time is going to be spent cleaning and filling out paperwork than looking after children. Consequently, the safety and quality of childcare might even be worsened.

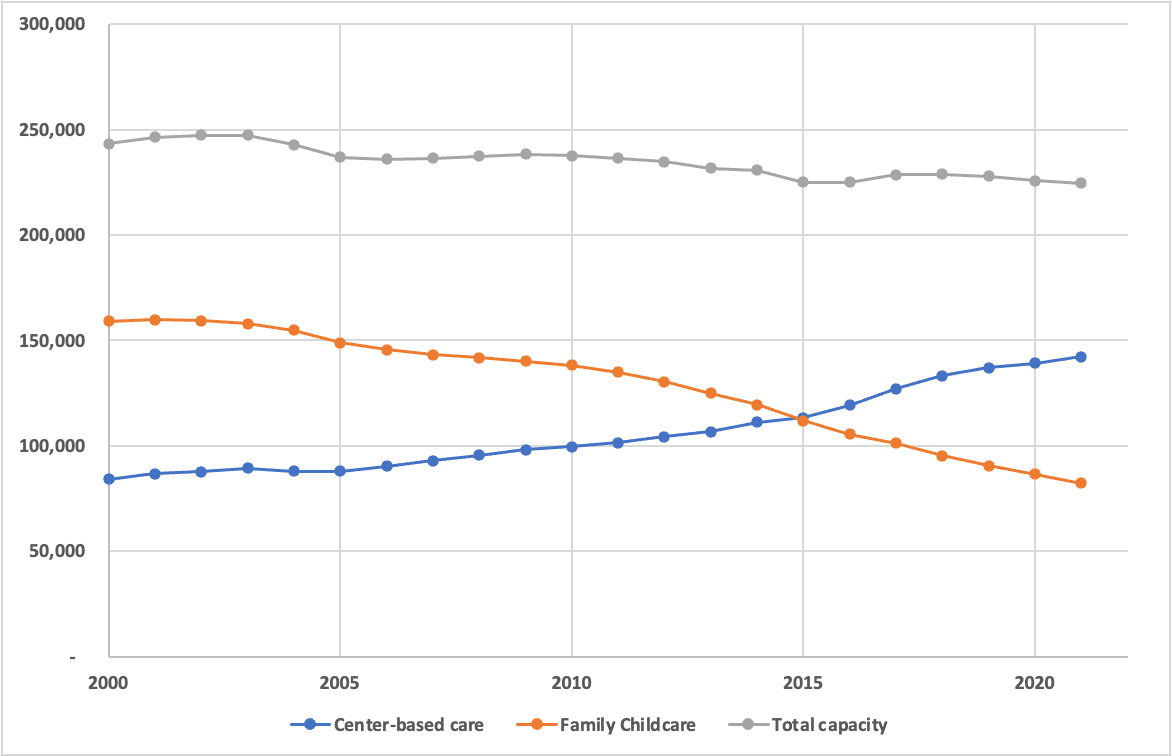

Family childcare providers are already leaving the industry

Generally, the number and share of family childcare providers in Minnesota has been dwindling over the years. While Minnesota had nearly 160,000 family providers in 2000, that number was down to 82,000 in 2021. In 2000, family providers made up nearly two-thirds of the total childcare capacity. In 2021, however, their share was down to about one-third.

While in the Metro region family providers have been replaced with centers, that hasn’t happened in greater Minnesota. Ergo, total childcare capacity has been on a downward trend since 2000.

According to DHS data (as reported by the Star Tribune), in 2024 Minnesota had 148,900 center-based slots and 71,200 family childcare slots for a total of about 220,000. This is over 20,000 slots fewer than the state had in 2000.

Figure 3: Childcare capacity by type of care, 2000-2021

While demographics are partly to blame for this trend, providers have also cited unfriendly regulations as a contributing factor. It should be concerning, therefore, that instead of addressing the crisis, the DHS is proposing rules that will worsen this trend. Given the already insane amount of rules that providers follow, creating new burdens is the least logical next step. That is, unless the aim is to kill home childcare providers.

What can you do

Currently, the DHS is hearing comments from providers as well as the public on the proposed draft. The DHS will revise the draft after July 15th, the last day for which anyone can make comments. The final draft will be presented to the legislature in the 2025 legislative session and lawmakers will decide whether to implement these standards or not.

As a business person, parent, or concerned Minnesota, you can take a survey or send an email to ppertzbqreavmngvba.quf@fgngr.za.hf and let the DHS know that Minnesota cannot afford to lose family childcare providers.

Family childcare providers are essential to the childcare industry, especially in greater Minnesota. They provide an important option to families who can’t afford centers. The DHS needs to make the job of family childcare providers easier, not harder.

This article was originally published at the Center of the American Experiment.