For two years, we greeted each day with the latest COVID death count. Now, as we move into a relatively normal summer health wise, daily reports of gas prices and inflation are fueling anxiety and uncertainty. Hello, Prozac.

Though opinions vary about the reasons for the gas crisis, one thing is indisputable: the Biden administration’s objective is to dramatically alter American energy sources and consumption.

It’s a plan that requires patience and pain, we’re told, as the president flies near and far on Air Force one and travels on the ground with motorcades.

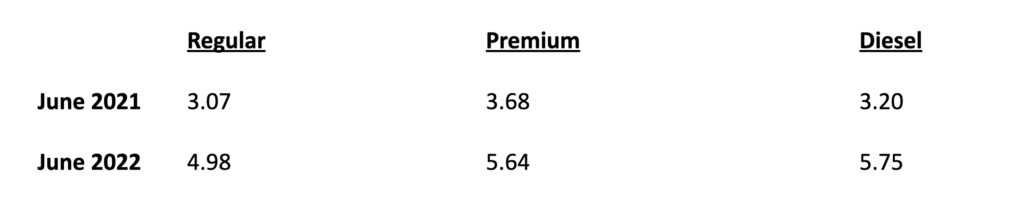

The numbers illustrate the Minnesota story for the past year and beyond.

For individuals, families, and businesses with a financial cushion, the call to be patient and absorb the increases won’t be life-altering.

But what about small businesses and people who live paycheck to paycheck, who may feel like a vacuum is attached to their bank accounts?

For the past 23 years, Kristi Frid, a graduate of St. Olaf, has operated a cleaning business out of West St. Paul.

Her clients run the gamut: homeowners; elderly folks on fixed incomes who can’t clean their own apartments; and churches and offices that might be facing reductions in revenue.

Driving in her minivan with three crew members, Frid traverses the metro: from Falcon Heights in the north to Lakeville in the south; from Woodbury in the east to Eden Prairie in the west.

She heads to Sam’s Club to purchase cleaning supplies and to fill up with regular gas three times per week, at a cost that is blowing her mind and blowing up her bank account.

Frid’s reluctantly confronting a new reality: she can’t continue to do what she’s done for so many years without making some difficult decisions and having some difficult conversations.

With her hourly rate $25 per man hour, the math is not in her favor. She needs to pay each crew member $16 to $19 per hour. Factor in insurance, gas, and cleaning supplies and her bottom line is worrisome.

“I have people who were paying $100 to have their homes cleaned and that was wonderful. Now, 15 years later, it’s like I’m working for free,” she says. It’s not sustainable.

To make a living (and save for retirement), Frid needs to raise her prices. She’ll address the issue with current clients, she says, and charge new clients a higher rate.

JR Galler is the maintenance division manager for Midwest Landscapes, based in Otsego, northwest of Minneapolis. Midwest offers snow removal, irrigation, landscape, and lawn maintenance services to homeowners’ associations and businesses.

Everything we do all day runs on fuel, Galler says — the vehicles they use to get to their jobs and all the small and large equipment they use to perform their jobs. They maintain pumps to house regular, premium, and diesel fuel, as their various equipment requires all of them.

Typically, they enter into contracts a year in advance. When they negotiated contracts last summer, they knew costs would go up, so they built in an extra $10,000 for fuel, Galler says.

They were way off.

Midway through 2022, fuel costs are up $80,000 over last year — about 30 percent.

Galler knows competitors are questioning whether it’s reasonable to ask customers for surcharges or increases. Midwest will honor existing contracts but include increases in new agreements, he says, noting it’s a risk of doing business.

Meanwhile, they’re looking at ways to improve efficiency. During COVID they cut back to two employees per truck; now they’re sending three.

But gas isn’t the only thing that’s gone up this year.

Midwest is paying 40 to 50 percent more for fertilizer.

Frid’s paying more for cleaning supplies and insurance.

These aren’t huge corporations that are positioned to weather significant increases. These are small businesses with lower wage employees who rely upon their employers to put food on the table — food that is costing much more than it did months or a year ago.

With inflation approaching 9 percent, Frid says her crew members are replacing chicken from Aldi with more rice and the cheapest beans they can buy. Instead of treating her crew to lunch at an ethnic restaurant, she’s switching to a fast-food option.

President Biden told the American people we’re going through a painful transition as we shift to green energy; that we just need to buckle up and bear down.

How will — and how long can — Americans go along with the “no pain, no gain” approach?