(Center of the American Experiment) — Minneapolis has now had four ranked-choice voting (RCV) elections and some patterns are emerging. The Nov. 2 general election was the fourth since 2009 to use the method, also known as “instant-runoff” voting.

It appears that the mechanics of RCV have pushed politics in heavily Democratic Minneapolis even further to the left.

This year the incumbent Minneapolis mayor, Jacob Frey, was re-elected to a second term. Although municipal elections in Minnesota are officially nonpartisan, Frey is a member of the state’s Democratic-Farmer-Labor (DFL) party.

No identified Republican has won an election for mayor of Minneapolis since 1957, when Paul Kenneth Peterson prevailed. Peterson left office in 1961 after serving two terms, losing his bid for a third. For the past 60 years, Democrats have exclusively served as mayor, with the exceptions of one independent serving and a Republican acting mayor holding office for a handful of hours.

In state and national races, Minneapolis voters tend to support the Democratic candidates with more than 80 percent of the vote. There are districts within Minneapolis where Donald Trump received less than 10 percent of the vote in the November 2020 presidential election.

In ranked-choice voting, rather than choosing a single candidate, voters are invited rank up to three choices for each office. If no candidate receives more than half of voters’ first choices, then second and third choices are added up, until one candidate obtains a majority of voters’ preferences.

The other distinguishing feature of RCV, as implemented in Minnesota, is the elimination of the primary election. All candidates from all parties compete in a single general election. In 2021, seventeen candidates appeared on the ballot line for Minneapolis mayor. In 2013, 35 candidates ran for mayor. The counting of ballots in 2013 took four days and 33 rounds.

Advocates for RCV, including the state’s main organization Fair Vote MN (tag line: “For more inclusive, representative democracy”), claim several benefits from the voting method. Obviously, the elimination of the primary round is seen as a plus, and having more choices among more candidates is touted as a benefit.

Voters who have to evaluate dozens of candidates to make three selections may disagree.

Since voters are encouraged (but not required) to rank 2nd and 3rd choices, RCV is said to encourage civility and discourage negative campaigning as candidates will want to gain votes from their opponents’ supporters. As stated by FairVote MN,

“By requiring candidates to win with a majority … candidates need to move beyond their base and build broad coalitions of support. Not only does the outcome more accurately reflect the will of the voters, but a more broadly accountable candidate makes for a more responsive officeholder.”

FairVote MN adds that,

“Candidates behave very differently when they benefit from second or third choice votes. They are less likely to attack an opponent since they don’t want to alienate that candidate’s base voters and risk losing their second choice votes.”

Throughout their website, FairVote MN references solving the problems of “extreme” candidates, “polarization” and “hyperpartisanship.”

But what if a locality routinely votes for one party 80 percent of the time in conventional elections? “Partisanship,” much less “hyperpartisanship,” is not the issue when most candidates and voters represent the same political party. In such instances, RCV tries to bridge the gap — not between left and right or Democrats and Republicans — but between left and lefter, in the case of Minneapolis.

Think of politics and political ideology as a football field. RCV imagines it is trying to bridge the gap between hostile parties camped on each side’s 40-yard-line. RCV tries to get candidates to move to midfield by appealing to the other side’s moderates. But if all the candidates are crammed into one end of the stadium, then RCV is bridging a gap between factions on the 9 and 11-yard lines. It is not moving politics back toward midfield, it is pushing politics toward one goal line.

In a one-party-city situation, the divide shifts to the natural fault line of the intraparty factions.

The actual mechanics of RCV also create some perverse incentives, as will be discussed below.

In pre-election polls, incumbent Mayor Frey held a comfortable lead over his 16 rivals, but was still short of a majority of votes in the first round. The same poll indicated that his two leading opponents were both Democrats (Sheila Nezhad and Kate Knuth).

As it happened, both Nezhad and Knuth supported Question 2, the anti-police referendum appearing on the same ballot as the race for mayor. Frey opposed Question 2.

In looking for second- and third-choice votes, the mechanics of RCV would push Frey to appeal to his leading opponents. With both favoring the well-funded Question 2 and with crime being the biggest issue in the campaign, Frey’s dilemma was this: how vocal could he be in opposition to this initiative, which would replace the existing city police department with an undefined Department of Public Safety? Should Frey search for 2nd choice votes among the centrist and right-leaning candidates who agree with him on this issue — but only represented about 5 percent of the electorate — or should he soften his stance to not alienate the 45 percent represented by his leading DFL opponents?

In the end, Question 2 was defeated, with a solid majority (56 percent) of the entire electorate voting against. However, from Frey’s perspective, the majority of this majority were already in his camp. To get to a majority in his race for mayor, Frey had to reach out to the minority (44 percent) seeking to end the police department.

The election revealed that a solid majority of Minneapolis voters favor law and order. But the election campaign at the top of the ticket revolved around the minority, anti-police viewpoint in an effort to maximize those lower-ranked choices.

On Nov. 2, Frey received 43 percent of the vote in the first round, with Nezhad at 21 percent and Knuth at 18 percent. Those were the only three candidates to advance to the second round of vote counting. Of the remaining 14 candidates, all were below five percent, and ten were below one percent each.

Although he opposed Question 2, as mayor, Frey presided over the 2020 riots in Minneapolis, which culminated in the burning of a police station. In addition, during his term in office, violent crime in Minneapolis has surged, with record or near-record levels of carjackings and murders.

With a majority of the Minneapolis electorate in favor of retaining the police department, the 2021 race for mayor should have been a referendum on Frey’s leadership of the department and how vigorous the city’s law and order effort should be going forward. The debate should have been between police and more police.

Instead, RCV ensured that the police debate between leading mayoral candidates was fought along the police/no police axis. With three choices in play under RCV, the voting method appears to move the ideological dividing line to the most leftward viable candidate.

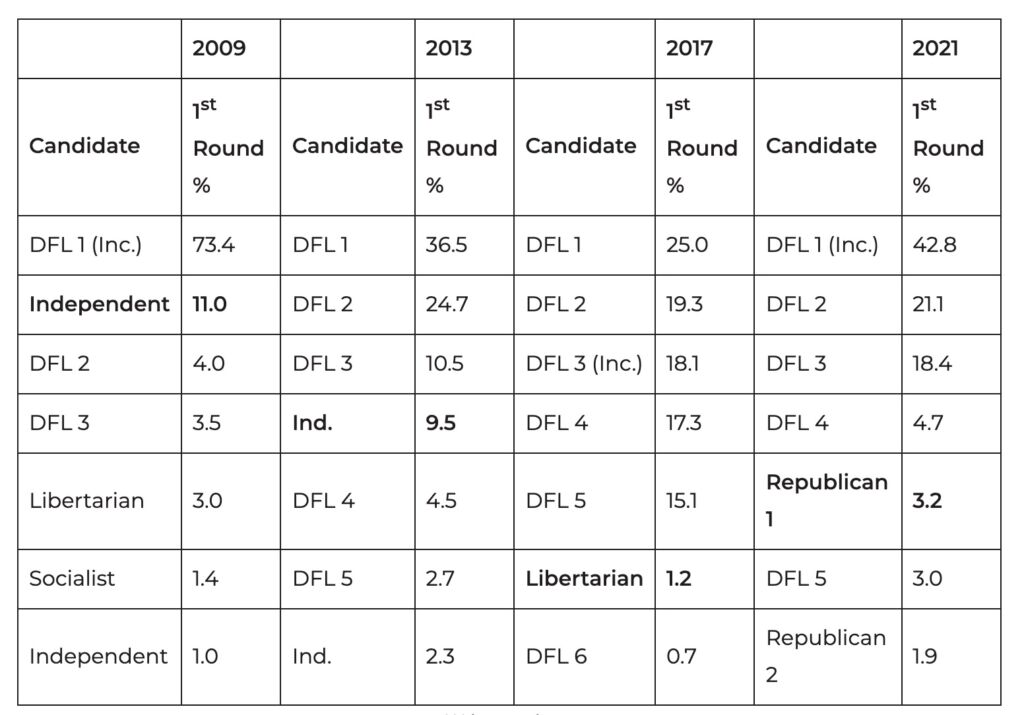

Here are the first round results from the last four Minneapolis mayoral elections,

The above table shows the top seven candidates for Minneapolis mayor and their respective share of first-round preference votes.

The 2009 contest resembled something approaching a two-party race. In 2013, the incumbent mayor chose not to run again. The top non-Democrat vote-getter in each year is shown in bold.

The three most recent mayoral elections have served more as a Democratic-party primary, albeit open to all voters, than a true general election. That is exactly the system that Minneapolis had in place prior to the adoption of RCV in 2009. In prior election years, an open primary election was held in September, with the top two vote getters (regardless of party) advancing to the November general election. The last non-Democrat to advance from the open primary was Barbara Carlson in 1997, a former Independent-Republican city council member. In the November 1997 general election, Carlson received 45 percent of the vote.

In 2009, under RCV, a Republican-endorsed independent candidate finished a distant second with 11 percent of the vote. In 2013, the Republican-endorsed independent candidate slipped to fourth place, receiving less than ten percent of the first-round preferences. In 2017, a libertarian candidate finished in sixth, getting a little over 1 percent. In 2021, Republicans staged a minor comeback, rising to fifth spot, with a little over 3 percent of the vote and placing a second candidate among the top seven.

If Minneapolis continues to use RCV to elect candidates, expect that the politics will drift ever further to the extreme.