Children’s Minnesota — one of the nation’s foremost pediatric health facilities — is closing down its St. Paul ICU and opening an inpatient mental health unit.

When the COVID-19 pandemic began, Minnesota’s public health officials were abuzz discussing ways to increase the state’s 500 bed ICU capacity. Now, nearly two years later, the state’s premier pediatric facility apparently needs more mental health beds than intensive care ones. This comes as a generation of youth are left struggling to pick up the pieces amidst the “new normal.”

Children’s Minnesota is one of America’s largest freestanding pediatric hospitals with the ability to house 380 patients between its two primary facilities in St. Paul and Minneapolis. It’s presently getting ready to add 22 more beds designated for mental health patients at its St. Paul location, transitioning the ICU beds over to the Minneapolis campus, per the Pioneer Press.

According to the science, mental health help for young people cannot come soon enough. Suicide attempts among girls ages 12-17 jumped just over 50% during the COVID lockdowns, per PEW Research.

Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy even issued an advisory in December 2021, calling national attention to sobering statistics about the lockdowns’ impacts on children. “Depressive and anxiety symptoms doubled during the pandemic, with 25% of youth experiencing depressive symptoms and 20% experiencing anxiety symptoms,” the advisory reads.

Also in late 2021, Minnesota’s Department of Human Services reported a 30% increase in kids showing up to ERs having mental health crises. About that same time, Children’s opened its first inpatient mental health facility.

The health system’s recent decision to allocate even more resources towards treatment of kids with severe mental health issues requiring acute treatment seems to be a continued acknowledgement of this problem.

The COVID lockdowns have deprived children of “key elements of childhood itself,” forcing them to spend “years of their lives away from family, friends, classrooms, [and] play,” UNICEF Executive Director Henrietta Fore observed in October of last year.

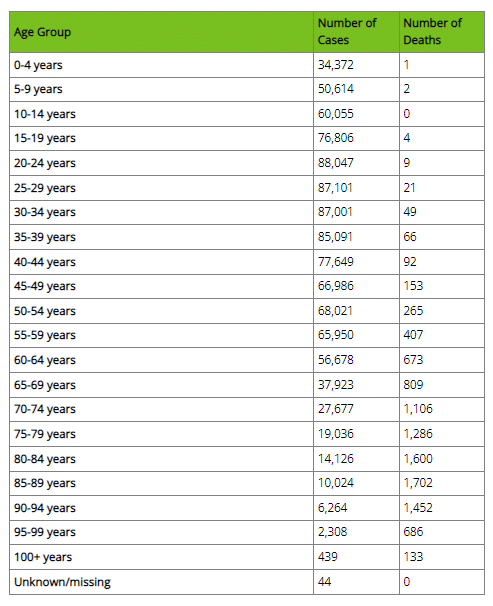

Meanwhile, lockdown critics suggest that subjecting kids to such extreme measures at the price of their mental well-being might not have been worth it. Children are not very susceptible to the virus, as evidenced by the incredibly low death rate among young people in Minnesota: only seven people under the age of 20 have been killed by coronavirus.