(Center of the American Experiment) — Back in 2020, Minnesota’s state government based much of its policy response to COVID-19 on a computer model, built over a weekend by the University of Minnesota School of Public Health and Department of Health. It was, to be blunt, a total failure.

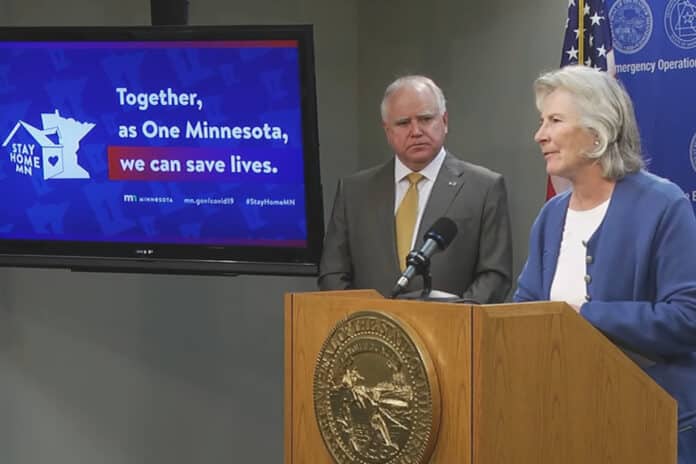

Version 1 debuted on March 25, 2020, and forecast that, without mitigation, COVID-19 could kill upwards of 74,000 Minnesotans and that the state’s 235 intensive care beds would be full within six weeks. On this basis, Gov. Tim Walz issued the initial stay-at-home order.

Version 2 debuted on April 8. This forecast that even with the measures Gov. Walz put in place, 22,000 Minnesotans would die of COVID-19 by October 2021. When Version 3 was released on May 13, its most optimistic scenario forecast 22,589 deaths in Minnesota over the course of the pandemic.

In fact, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as of today, nearly two years on from the point when COVID-19 was supposed to have killed 22,000 Minnesotans, the actual number is 4,442.

In October 2020, we were told that a new version was in the works. Since then, no more has been heard of Minnesota’s once lauded COVID-19 model.

But taxpayers’ money won’t waste itself. So, as the Star Tribune reports:

“Minnesota is using a $17 million federal grant to learn from the pitfalls of COVID-19 forecasting in the last few years and to improve its predictions for the next outbreak.

Better estimates of cases of an infectious disease and how it spreads could improve responses and target them at high-risk regions or populations rather than the entire state, said Dr. R. Adams Dudley, a University of Minnesota health informatics professor who is co-leading the effort.

Better estimates also could prevent the damage that occurred during the COVID pandemic when wayward predictions undermined public confidence in the government’s quarantine orders and restrictions.

‘Think about the public trust cost of being wrong,’ Dudley said.”

There is a lot to unpack there.

First, the idea that we should target responses “at high-risk regions or populations rather than the entire state” is exactly what many were arguing for at the time. I wrote in November 2020 that:

“Covid-19 is like a laser guided missile designed to kill the elderly, especially those in care homes.”

Gov. Walz would have been better off focusing on the state’s care homes rather than, in the face of all the evidence, shutting down every bar, gym, and cinema in Minnesota.

Second, “wayward” is an exceptionally gentle word to describe estimates that were off by several orders of magnitude. This is one arm of Minnesota’s establishment looking out for another.

And, third, the loss of public trust isn’t the only cost of getting it so horrendously wrong. Research suggests, among other things, that closing down schools during COVID-19 could cost each impacted student $70,000 over the course of their careers, or roughly $28 trillion in total, and that the COVID-19 recession will cause 59,000 deaths annually for next 15 years.

We are only now becoming aware of the costs of the COVID-19 pandemic and of federal and state government responses to it. These overreactions were at the very least justified by models, like Minnesota’s, that weren’t worth the microchips they were coded on. Here is a bit of advice that won’t cost $17 million: admit in the future that these estimates are highly speculative and form a weak basis — at best — for a public policy response.