Early in 2019, a firestorm of criticism descended upon veteran journalist Tom Brokaw because he said on NBC’s Meet the Press that Hispanics “should work harder at assimilation” and shouldn’t isolate themselves “in their communities.” NBC condemned his comments as “inaccurate and inappropriate,” media outlets ran articles and editorials calling them racist and factually wrong, and Brokaw apologized.

Contrary to the blowback against Brokaw, scholarly sources show that modern Latino immigrants are not assimilating like previous generations of immigrants. Furthermore, this is having negative economic impacts on them and the nation at large. These facts have nothing to do with race and everything to do with factors that can foster or impede economic prosperity.

Rejecting the Melting Pot

While berating Brokaw for his remarks, the National Association of Hispanic Journalists claimed: “To assert that the U.S. is not the melting pot that the country prides itself on being, is disinformation as the U.S. has always had immigrants and a mixture of races, religious beliefs and languages in its history.”

That statement is demonstrably untrue, as the popular culture and academia are now rife with people who reject the idea of the U.S. as a melting pot. Instead, they insist that the U.S. is and should be a “salad bowl” in which people mix but remain culturally distinct. The editors of the academic serial work American Immigration: An Encyclopedia of Political, Social, and Cultural Change explain that this trend is a substantial departure from the past:

As a nation of immigrants and their descendants, the United States has been described over the centuries as a “melting pot” of cultures. Today, most immigration scholars and activists eschew that term, contending that it implies a loss of native culture and an assimilation process that turns peoples of diverse backgrounds into a single, culturally homogenized populace.

In the same book, Aonghas Mac Thomais St.-Hilaire of Johns Hopkins University sheds more light on this phenomenon:

Since the 1960s, as a result of ethnic revival efforts by African Americans, Latinos, and indigenous peoples, multiculturalism has emerged as a dominant ideology in the United States, and it competes with the century-old ideology stressing the importance of complete assimilation to Anglo-American norms, altering the playing field for post-1965 immigrants and their offspring.

No longer does American society expect—nor can it expect—immigrants and their children to follow traditional patterns of cultural adaptation, by which the culture, language, and values of the country of origin are entirely abandoned for those of the United States.

This sea change, which the National Association of Hispanic Journalists falsely denied, has profound implications. For if immigrants come to the U.S. with views and cultural norms that caused poverty in the nations they left, they now tend to keep them instead of adopting new ones that promote prosperity.

Productivity, Communication & Earnings

More than anything else, material prosperity springs from productivity, or the amount of goods and services that people produce in an hour of work. As explained by former Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen and other economists, “the most important factor determining living standards is productivity growth.”

In turn, a primary driver of productivity is communication, which enables people to share information and work together more effectively. The converse also applies, and restricted communication often begets poverty. In Africa, for example, economic development has been limited by linguistic diversity, as Africa has about 10% of the world’s population and about 30% of the world’s languages.

Likewise, a 2014 study by the Brookings Institution found that U.S.:

- workers with limited English proficiency “earn 25 to 40 percent less than their English proficient counterparts.”

- “high-skilled immigrants who are not proficient in English are twice as likely to work in ‘unskilled’ jobs (i.e. those requiring low levels of education or training) as those who are proficient in English.”

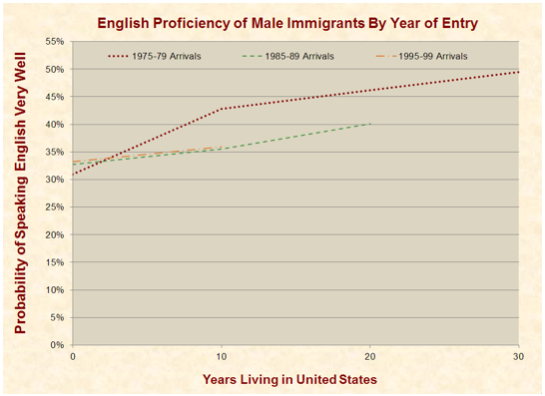

Contrary to pseudo-statistics circulated by the press, recent generations of immigrants have not developed English proficiency like those in the past. A 2017 analysis by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine found that male immigrants who entered the U.S. in 1985–89 and 1995–99 made significantly less progress learning to speak English than those who entered in 1975–79:

The above data is grounded in a 2015 paper in the Journal of Human Capital. Yet, the media is spreading the opposite belief by appealing to a source that distorts another source that distorts its sources. To wit, a Washington Post commentary by Paul Waldman cites a 2015 report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine that claims “today’s immigrants are actually learning English faster than their predecessors.” In turn, this report cites a 2006 book that doesn’t show that. Worse still, the book doesn’t even show what it claims to show.

The book, Century of Difference: How America Changed in the Last One Hundred Years, contains a chart (on page 43) showing that about 45% of immigrants who arrived in 1900–1920 learned to speak English after they came to the U.S., as compared to only 16% for those who arrived in 1980–2000. Thus, the book doesn’t support and actually contradicts the claim that recent immigrants are “learning English faster than their predecessors.”

However, the book misleadingly asserts that recent immigrants have higher rates of “English proficiency” than those from a century ago because more of the recent ones knew English when they arrived. It says that 45% of immigrants who came to the U.S. in 1900–1920 were able to speak English when they arrived and that 90% of them had this ability after 20 years. In comparison, it claims that 80% of immigrants who came to the U.S. in 1980–2000 were able to “speak English on arrival” and that 96% of them had “English proficiency” after 20 years.

In other words, the book alleges that only 4% of modern immigrants weren’t proficient in English after 20 years. Contrast that 4% figure with the chart above showing that 60% of recent immigrants weren’t proficient in English after 20 years. Why the massive difference? Because despite what the book claims, it does not show rates of “English proficiency.” Instead, for modern immigrants, it shows rates for a lower threshold of language ability that corresponds to being able to speak English “not well.”

The book’s misleading verbiage is underscored by the fact that a 2015 study by Pew Research found that 61% of “immigrant Latino adults who have been in the U.S.” for more than 20 years cannot “speak English proficiently.” Whereas the book claims that only 9% of “recent immigrants from Latin America” have not achieved “English proficiency” after 20 years.

Meanwhile, for older immigrants, the book uses a completely different measure based on whether Census workers in the early 1900s wrote a simple “No” or “Yes” when evaluating if people “can speak English.” Hence, the century-old and modern datasets are not comparable. Furthermore, the book ignores data from the 1960s through 1970s and places all immigrants from 1980–2000 into a single group. This cloaks the changes that occurred in the era when multiculturalism replaced assimilation.

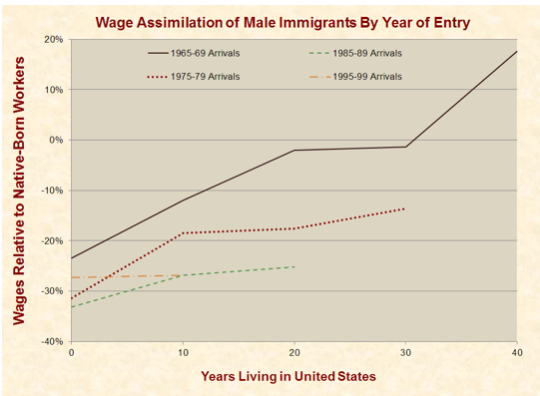

In accord with declining rates of English proficiency, recent immigrants are failing to increase their wages like earlier generations. Those who arrived in the U.S. during 1965–69 started out by earning an average of 24% less than native-born workers of the same age—but they rapidly advanced—and forty years later, they were earning 18% more than native-born workers. Later generations of immigrants have done progressively worse in this regard, and the most recent one has been stagnant:

The failure of recent immigrants to learn English and thereby improve their productivity and wages harms not only them but society in general. This is because poor immigrants:

- add to the rising costs of means-tested welfare.

- reduce the average productivity of society, which has serious negative consequences.

- likely depress the wages of other low-skilled workers, particularly those without high school diplomas.

On the other hand, low-skilled immigrants reduce consumer prices for the products and services they supply. However, this mostly benefits wealthier people because they consume more products and services produced by low-income immigrants, such as child care, restaurant meals, house cleaning, landscaping, taxi rides, and construction.

Because many low-skilled immigrants work in agriculture, some assume that they keep the prices of fresh produce low, but a recent study from the Giannini Foundation of Agricultural Economics at the University of California found that if farm worker wages increased by 40%, average spending on fresh produce would rise by only $21 per household per year. This is because “Americans do not spend much on fresh fruits and vegetables,” “farmers receive only a third of what consumers pay for produce,” and “farm labor costs are usually less than a third of farmer revenue.”

Corruption

Beyond communication and earnings, another important aspect of assimilation is related to corruption, which goes hand-in-hand with poverty and is rampant in the nations that send the most immigrants to the United States. For instance, a 2009 Pew survey found that 51% of Mexicans had in the past year done a favor, given a gift, or paid a bribe to a “government official in order to get services or a document that the government is supposed to provide.”

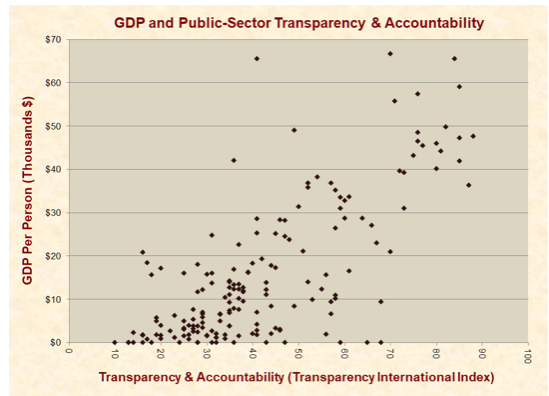

If these immigrants arrive with such mindsets and keep them, this can cause enormous damage to a nation. In 2011, the EPPI-Centre at the University of London published a systematic review of 115 corruption studies which found that “corruption has negative and statistically significant effects” on economic growth, both “directly and indirectly.” Though association does not prove causation, data from 180 countries shows that the link between poverty and corruption is real and striking:

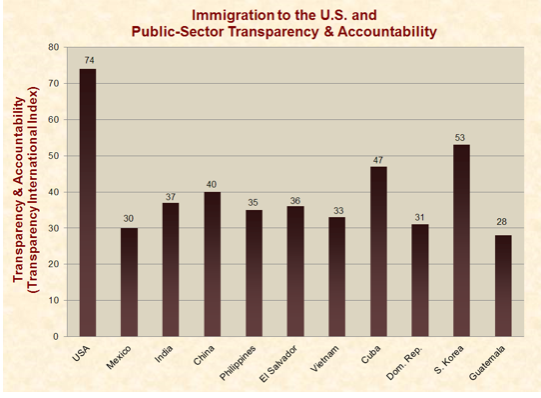

A recent video op-ed by the New York Times rife with misinformation claims “there are specific times and places where you could confuse America for a developing country, as elections are tampered with,” “citizens don’t trust uniformed officers,” and a “a dual system is emerging when public services are for sale for the highest bidder.” In reality, the U.S. has much higher levels of public-sector transparency and accountability than developing nations, particularly those that send the most immigrants to the U.S.:

Effects on Government

Immigrants who don’t assimilate can also undermine the policies and institutions that have helped make the U.S. so prosperous that even the poor are richer than the average for all people in most developed nations. In this respect, modern immigrants are moving America to the political left, especially Hispanic immigrants:

- A nationally representative bilingual poll of 784 immigrant Latinos commissioned by Pew Research in 2011 found that 81% said they would prefer “a bigger government providing more services,” and 12% said they would prefer “a smaller government with fewer services.” In stark comparison, 41% of the general U.S. population say they would prefer a bigger government, and 48% said they want a smaller one.

- A 2012 poll of 2,900 immigrants who were U.S. citizens found that 62% identified as Democrats, 25% as Republicans, and 13% as Independents.

- A nationally representative bilingual poll of 800 Hispanic adults conducted by McLaughlin & Associates in 2013 found that 59% were born outside the U.S., 53% considered themselves to be Democrats, 12% considered themselves to be Republicans, and 29% considered themselves to be independents or another party.

Advantages

Despite the harms caused by a lack of assimilation, it also has some advantages, and the U.S. could benefit by adopting some aspects of foreign cultures.

For example, U.S. lifestyles are generally not conducive to good health, and U.S. Latinos have significantly longer lifespans than U.S. whites. While these added years of life may be related to genetic factors, they may also be due to certain hallmarks of Hispanic cultures, like strong family and social ties, which correlate to better health.

St.-Hilaire also notes that assimilation to their local surroundings can economically harm immigrants because many of them only have enough money to “settle in inner-city neighborhoods” where:

- the prevailing U.S. “youth culture is profoundly anti-academic, regarding ‘studious’ as a socially undesirable epithet.”

- young native-born Americans “perpetuate an oppositional culture that hinders them from acquiring the skills needed to succeed in American society.”

Summary

The changing attitude of immigrants toward assimilation has been transforming the U.S. from a melting pot to a salad bowl. This is having harmful economic effects, especially on immigrants who don’t assimilate but also on the nation as a whole.

These harms are driven in part by declining rates of English proficiency, which limit their ability to communicate, and thus, their productivity and earnings. Other factors that may play a major role are their mindsets toward corruption, social institutions, and government policies.

Conversely, some elements of foreign cultures are associated with better outcomes than those of the U.S., and these can help immigrants and native-born Americans alike.

Some consider multiculturalism to be a universal good, while others deride it. By putting aside such ideologies and examining facts, people throughout the world can harvest the good aspects of foreign cultures and scrap their harmful ones.

James D. Agresti is the president of Just Facts, a think tank dedicated to publishing rigorously documented facts about public policy issues.