Across Minnesota crimes are surging, carjackings are at an all-time high, and Minneapolis alone is on a record pace for homicides this year.

Minnesotans have had enough and some whistleblowers have turned to Alpha News to sound off about the MN Department of Corrections (DOC) which allows repeat offenders to “get a slap on the wrist” and be released.

“They are not returning them to the prisons when they [criminals] continually ignore rules, use drugs, or even commit new charges,” a source directly familiar with DOC operations tells Alpha News.

Stories like Devon Dwayne Glover, who violated his release term are prime examples of DOC’s apparent failure to keep dangerous criminals off the streets. In April 2017, Glover exchanged gunfire in a crowd on the Dale Street light rail in St. Paul. A bystander was hit and wounded by his bullet.

After three years and additional convictions, Glover was again accused of dangerously firing his gun in June 2020. Glover and another man shot a Bloomington restaurant owner during an attempted robbery. Both men were charged with attempted murder.

Growing trend of repeat violations

Alpha News was told by multiple sources more violators are now able to avoid going back into prison after committing a new crime because their early release conditions get modified or “restructured.”

One source familiar with this trend describes “overwhelming amounts of violators with revocation hearings that say ‘restructured.'”

“I can tell you one thing, there’s an unbelievable amount of releases from a max security prison,” the source also observes. “We weren’t designed to release inmates from max security. There’s now a lot more you’re seeing than ever before.”

Another person who did not want to be named described several occasions where offenders were not sent back to prison after violating parole.

“I witnessed an offender who was on early release who had been caught driving after revocation twice, be allowed to stay out in the community. I saw an offender who has been living in a DOC funded house who was given a thinking report for using meth. An agent caught an offender drinking 3 days after being released, when the agent called for a warrant the Hearings and Release unit denied it,” the source told Alpha News.

Concerned DOC staffers weigh in

An internal ombudsman’s report included several anonymous DOC interviews where most expressed support to reduce the prison population as well as decrease parole revocations for smaller or technical offenses. However, “many felt that while the shift was positive overall, it had swung too far.”

In the report, DOC staffers say it’s become hard to get a revocation hearing “even for new, more serious offenses such as assault or being in possession of or in the presence of a firearm.”

Employees also believed that “supervising agents are losing authority and it is becoming increasingly difficult to enforce conditions of release.”

Staff now feel that offenders “do not have motivation to change their behaviors because they know they will not be revoked or feel that they have ‘a few freebies,'” per the ombudsman’s report.

Challenge Incarceration Program

Challenge Incarceration Program (CIP) is an early release program that give felons a chance to be out in the community under certain conditions.

State statute 244.171 governs CIP. With regards to sanction, the law states, “the commissioner shall provide for revocation of intensive community supervision of an offender who:

- commits a material violation of or repeatedly fails to follow the rules of the program;

- commits any misdemeanor, gross misdemeanor, or felony offense; or

- presents a risk to the public, based on the offender’s behavior, attitude, or abuse of alcohol or controlled substances. The revocation of intensive community supervision is governed by the procedures in the commissioner’s rules adopted under section 244.05, subdivision 2.

Supervised Release Program

According to MN state statues “every inmate shall serve a supervised release term upon completion of the inmate’s term of imprisonment as reduced by any good time earned by the inmate or extended by confinement in punitive segregation pursuant to section 244.04, subdivision 2.”

If an inmate violates the conditions of the inmate’s supervised release imposed by the commissioner, the commissioner may:

(1) continue the inmate’s supervised release term, with or without modifying or enlarging the conditions imposed on the inmate; or

(2) revoke the inmate’s supervised release and reimprison the inmate for the appropriate period of time.

Intensive Supervision Release

The Intensive Supervision Release (ISR) requires that certain high-risk offenders be identified while in prison, and that those offenders be placed on ISR upon release from prison.

Offenders remain on ISR until they successfully complete the program or until they reach expiration of their sentence. Those under ISR have strict rules including unannounced agent visits, a zero tolerance for drug/ alcohol use, and intense surveillance.

“Offenders face return to prison for violation of ISR program rules. ISR revocations are in accordance with DOC Guidelines for Revocation of Parole/Supervised Release and Promulgated Rules, administered by the DOC Hearings & Release Unit,” per the DOC.

Decline in DOC revocations

The ombudman’s report shows DOC revocations in 2020 were down 45 percent in an effort to prevent the spread of COVID-19. According to one analysis, in early November, Minnesota had the “the sixth highest infection rate among prison inmates in the country and the third highest among corrections staff,” and during one week in November had the “highest rate of new inmate cases in the nation.”

While infection rates increased rapidly, whistleblowers believe there’s another reason for the administrative restructuring of prison population in Minnesota: a desire to reduce the proportion of inmates who are people of color.

“It’s to release more inmates because our population is disproportionate with the facilities. This is all the whole Floyd riots and what they call a ‘racial disparity,’” one source said.

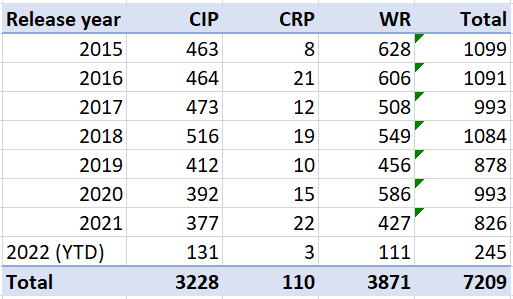

Contrary to what sources have told Alpha News, according to DOC data, less inmates have been put on early release programs.

CRP = Conditional Release Program

WR = Work Release

2022 figures are through 4/30/2022 (Dept. of Corrections)

Of the 7522 people in the 5/1/2022 MN prison custody population, 1021 have previously spent time on ISR.

DOC response

A spokesperson for the DOC tells Alpha News the institution is doing everything in its power to help people transform their lives when they are sent to prison because “95% of them will eventually be released back into the community.”

“That’s why [we] review each supervised release violation individually to make a determination of how best to protect public safety. In many cases it means people return to prison,” a DOC spokesperson tells Alpha News. “We also know from the data that in some cases it is more effective to get a person connected to treatment and other resources in the community rather than putting them temporarily in prison, which is often for very short periods of time in these cases.”

The spokesperson added that when someone returns to prison for short periods of time, it’s not enough to get them the programming they need and “they can come out worse off than when they came in.”