As violent juvenile crime explodes across the Twin Cities, police and local leaders are at their breaking point—forced to watch repeat offenders walk free because there’s nowhere to hold them. And yet, in Minnetonka, a sprawling $30 million juvenile facility built to rehabilitate troubled youth has sat unused since 2021.

The question so many are asking: why is this resource being wasted while chaos grows on our streets?

Alpha News spoke with a police officer in Hennepin County, who requested anonymity, about the dire state of the juvenile justice system, where auto thefts, gun possession, assaults, and robberies appear to be the new norm. According to the Star Tribune, juvenile homicide rates more than doubled between 2021 and 2023 compared to the three years prior.

The officer described it as a “revolving door,” where serious offenders face little to no consequences.

“These kids commit serious crimes and are back on the streets because there’s nowhere to house them,” the officer said. “They cut their ankle monitors off and go out and commit more crimes. Their parents don’t know what to do with them. They’re asking for help, but our hands are tied because there is nowhere to place them.”

The officer expressed frustration and confusion over the continued closure of the Minnetonka facility, commonly known as the County Home School.

The juvenile correctional facility was operated by Hennepin County for over a century and offered a residential setting where youth could participate in correctional programming and receive essential services.

A shuttered resource in Minnetonka raises questions among police and legislators

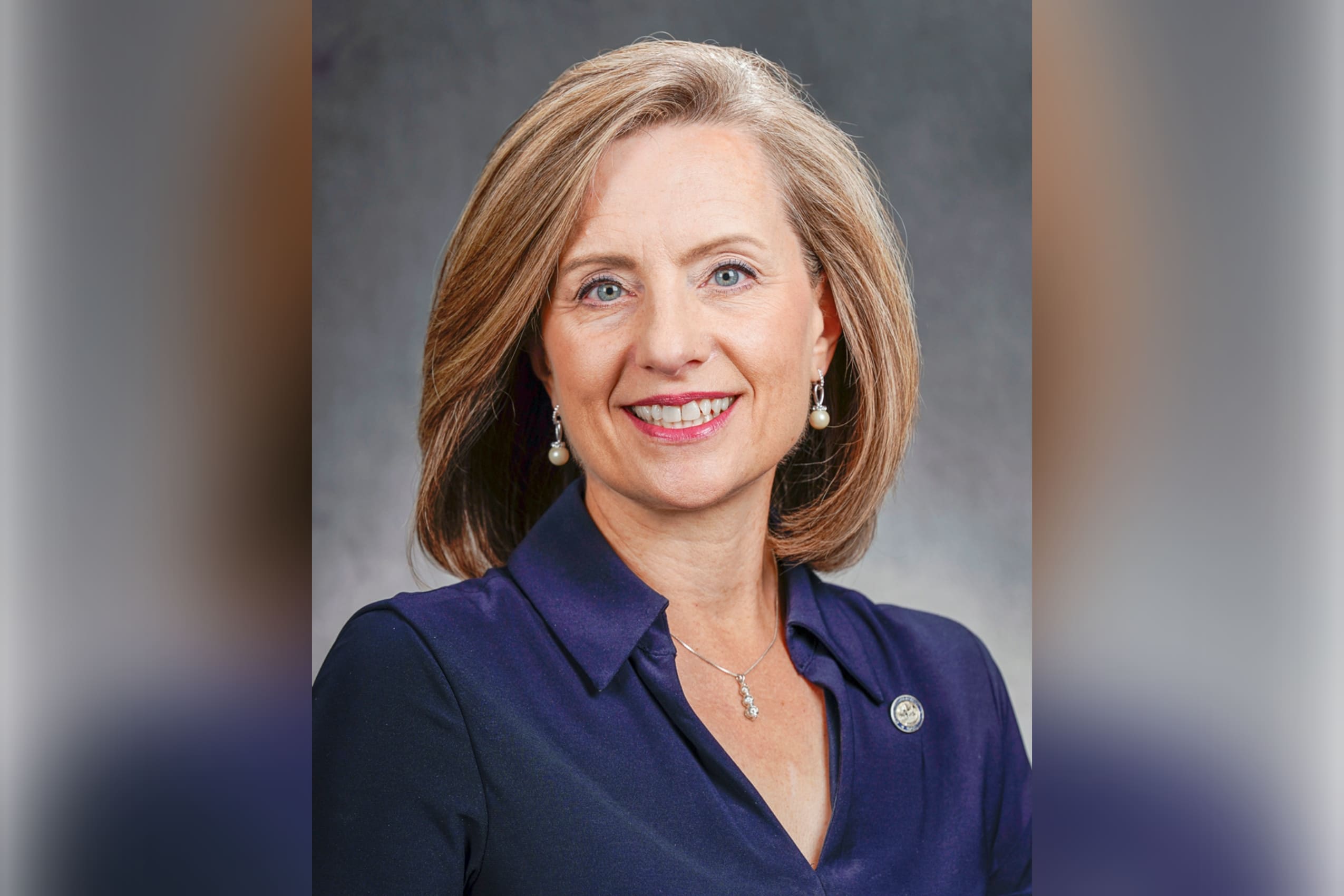

Rep. Kristin Robbins, R-Maple Grove, recently toured the County Home School alongside Rep. Paul Novotny, R-Elk River, the incoming chair of the Public Safety Committee, and spoke exclusively with Alpha News about it.

Robbins said her interest in the facility was sparked by repeated complaints from constituents and police officers, who told her there’s “really no place” locally to detain juveniles for serious offenses—a role the County Home School once served.

“The officers go through all the work of bringing these kids downtown, going through the process—it takes two officers off the street—and then they’re not held because of a lack of resources,” said Robbins. “The concern is that these kids, especially in the carjacking cases, are often the same ones—repeat offenders—and they’re not getting help or breaking the cycle of crime.”

Robbins recounted a ride-along with the Hennepin County sheriff and a deputy where she witnessed this “broken system” in action.

“We dealt with a carjacking involving two 16-year-olds in Plymouth. They were cited and brought home. I mean, it was a serious incident, but there was nothing else to do, and it was kind of stunning to me,” she said.

Robbins told Alpha News that she has been investigating not only the decision to close the facility but also the lack of transparency and oversight surrounding it.

“We’re sending metro kids far away rather than utilizing a facility right in our backyard, where they could stay connected with their families and access services locally,” Robbins said. “The fact that Hennepin County staff made this decision without a vote by the county board—despite objections from juvenile court judges who believed it wasn’t in the best interest of the juveniles—is truly stunning to me.”

Critics blast the closure without a working alternative

Among the most vocal critics of the County Home School’s closure was now-retired Judge Tanya Bransford, who in 2021 expressed serious reservations about the decision, particularly the consequences of sending youth far from their communities.

“People argue that we should just not have any children detained. That’s not reality,” Bransford told the Minnesota Reformer at the time. “If you have people charged with murder, they have to be detained … I’m concerned that they’re going to wind up being sent out of state or other places that we don’t have control over.”

A 2024 University of Minnesota paper notes that Hennepin County has the highest rate of youth prosecution in Minnesota but no local residential treatment program for incarcerated youth.

“The decision to close the Hennepin County Home School in 2021 removed the one local option for treatment programming. These youth wait in the Juvenile Detention Center, with no access to this programming, until a bed becomes available outside of the metro counties,” an abstract of the paper reads.

Robbins stressed both the human and financial costs of the decision.

“It’s not only hard on the kids being so far away from their homes, but it’s also a huge transportation cost for the state or the county to take officers off their duty to transport them securely to the juvenile detention centers in Red Wing or Moorhead, and then to transport them back and forth for different hearings,” stated Robbins, who added that she was told some juvenile offenders are being sent as far away as Utah—something Hennepin County Commissioner Kevin Anderson says is not true.

“No juvenile offenders have been placed in a facility in Utah,” said Anderson in a statement to Alpha News, though he conceded that some placements have been made in “other states.”

“Overall, the number of youth being sent out-of-state is trending downward in Hennepin County,” explained Anderson. “Sometimes there is no in-state program available to meet the needs of the youth. Most of Hennepin County’s out-of-state placements are in Wisconsin, consistent with our practice to keep youth as close to home as possible.”

As for why the Hennepin County Home School closed in the first place, Anderson explained, “It closed in 2021 due to declining use, increased operational costs, outdated facilities, increased availability of community-based services, and community input and research. ”

Future of the facility

The future of the sprawling campus remains in limbo, with Robbins stating she’s heard that Hennepin County may be planning to bulldoze the facility.

“I’m not sure it’s in the taxpayer’s best interest that a $30 million facility gets torn down,” said Robbins, who admits she was surprised by how good of shape the facility was in.

“When we did the tour, we were kind of expecting it to be fairly run down, but to me, it’s in as good shape—or potentially better shape—than the active facility I toured in Red Wing,” Robbins said.

Robbins said the property featured horse barns for equine therapy, as well as a baseball field, soccer field, and wooded trails for recreation. Inside, the facility included modern classroom spaces with whiteboards, science labs, a gymnasium, a stage, and even a grand piano. Vocational training opportunities, such as welding and electronics repair, were also available.

“These kids were getting exposed to opportunities to find other ways to manage their lives,” said Robbins, who described the facility’s offerings as “a full school program of math, reading, and science.”

Alpha News reached out to Hennepin County Attorney Mary Moriarty with questions regarding the closure of the County Home School, the adequacy of the current juvenile justice framework, and the future of the $30 million facility. However, no response was received.