Three residents of Bloomington are suing the city over its rejection of a ballot measure looking to repeal ranked-choice voting (RCV).

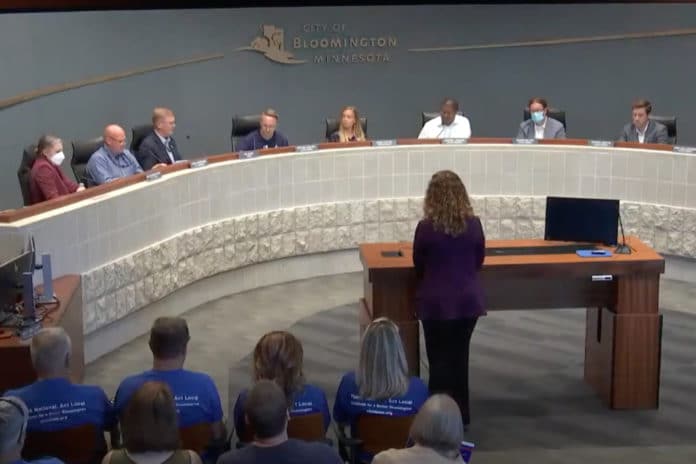

The lawsuit was filed last Thursday, according to a press release from the Upper Midwest Law Center (UMLC), the legal group representing the three residents. The lawsuit challenges the Bloomington City Council’s unanimous rejection of a charter amendment on the November ballot to overturn the 2020 implementation of RCV.

At a city council meeting on Aug. 8, city attorney Melissa Manderschied recommended that the council reject the charter amendment on the grounds that it was “manifestly unconstitutional and inconsistent.”

The proposed amendment would repeal RCV in Bloomington and require support from two-thirds of voters for any future amendment to adopt RCV.

In a July advisory opinion to city attorney Manderschied, assistant attorney general Jacob Campion argued that the city of Bloomington could not “lawfully” allow a two-thirds approval requirement to amend the city charter because Minnesota Statutes only allow for a 51% approval requirement.

“The 51 percent approval threshold is not a ‘general law’ that charter cities can contradict through their powers,” Campion wrote. “It is our opinion that Bloomington cannot set a two-thirds approval requirement to amend its charter.”

The residents, however, object to the city’s characterization of the ballot measure language as “manifestly unconstitutional.”

“Even if one assumes for purposes of argument that the one procedural matter on the proposed amendment is unconstitutional, the City still should have placed the completely distinct remainder of the proposed amendment on the ballot,” the lawsuit reads. “Minnesota Supreme Court precedent clearly contemplates that portions of proposed charter amendments may be severable as long as the overall amendment is not ‘substantially emasculated’ by the omission of the unconstitutional part.”

In a statement, UMLC senior trial counsel James Dickey also criticized the City Council for using a “secondary part” of the proposed ballot measure as an excuse to toss out the entire measure.

“Probably the worst part of Bloomington’s actions here is that they only objected to one secondary part of the proposed charter amendment, which is unrelated to the meat of the amendment. They didn’t object to anything else, yet they tossed out the whole thing,” Dickey said. “We believe the courts should and will correct this government overreach.”

In November 2020, a charter amendment implementing RCV in Bloomington passed with just 51.2% of the votes. A group called Residents for a Better Bloomington believes RCV is a “convoluted and controversial experiment,” and collected 3,300 signatures to get the issue back on the ballot this year.

“Well-heeled proponents of RCV — outside Bloomington — unleashed a withering, highly sophisticated, and staggeringly expensive lobbying/public relations campaign to impose RCV on a citizenry with many serious questions and concerns,” the group said in a statement earlier this summer.

They said FairVote Minnesota, an affiliate of the national FairVote organization, provided 98% of the funds to bring RCV to Bloomington. RCV is currently used in five Minnesota cities: Minneapolis, St. Paul, Minnetonka, St. Louis Park, and Bloomington.

“In ranked-choice voting, rather than choosing a single candidate, voters are invited to rank up to three choices for each office,” explained Bill Glahn of the Center of the American Experiment. “If no candidate receives more than half of voters’ first choices, then second and third choices are added up, until one candidate obtains a majority of voters’ preferences.”