Over the last week, many governors have reinstituted coronavirus policy implementations which had been in various phases of cessation. Why? This is because of an alleged “spike” in new COVID-19 infections. Other states have abbreviated their phased lifting of lockdowns. This is despite the fact that current US deaths from COVID-19 are now 90% off their peak.

Washington State is considering criminalizing the refusal to wear a mask. New York State governor Andrew Cuomo has imposed new out-of-state visitor bans (with the comment that “in addition to law enforcement, [he] … expect[s] individuals such as hotel clerks … to question travelers from select states”). Democratic Presidential candidate Joe Biden’s comments that if he were to win the presidency, a federal mask mandate may follow. The Speaker of the House quickly voiced her support for that measure.

These and other developments suggest that rather than approaching the end of the government-created crisis, we may be at the threshold of a new beginning. That the recent rise in infections is mostly an artifact of massively expanded testing capabilities seems to occur to no one in the government or media. Equally unnoticed is that the apparently much wider spread of COVID-19 infections, many of which show middling symptoms or are treated as annoyances, should result in a decrease of concern: it appears that many times the number of people estimated early on have been infected by the novel coronavirus to little or no consequence.

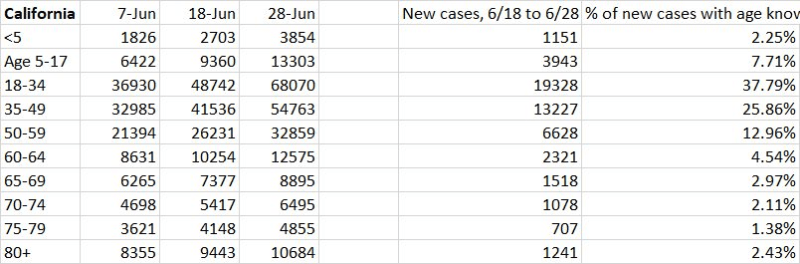

And further still, that some of the spike is accountable to the civil unrest in the wake of the murder of George Floyd. The prevalence of new COVID-19 infections among mostly Gen-Zs and Millennials (beside their prevalence in jobs that require COVID testing, such as in the fast food and service industries) undoubtedly had much to do with the disingenuity of political officials who ordered them to stay home, out of work and away from social occasions, yet responded with deafening silence as protests, demonstrations, and rioting broke out.

Note the recent data trend in California:

Or in Minnesota:

As other statistics regarding the toll of the novel coronavirus outbreak firm up, certain patterns are beginning to come into focus. With increasing certainty we can say that locked down states have seen four times the death toll of those which did not. The effectiveness of masking is, as well, being revealed as suspect, as is social distancing in the absence of testing and contact tracing (the efficacy of the latter of which is additionally questionable).

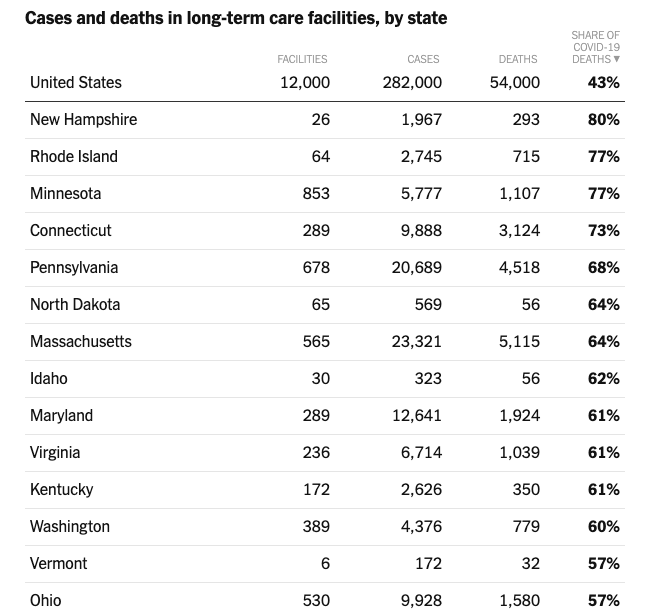

A more important revelation of the ongoing deluge of data has been either missed (or ignored) by the press. At AIER, we noted the stunning death rates in long-term care facilities back in the third week of May.

Just a few days ago, the New York Times reported that 54,000 deaths due to COVID-19 — 43% of all deaths in the United States — occurred in nursing home residents and workers:

In 24 states, the number of residents and workers who have died accounts for either half or more than half of all deaths from the virus. Infected people linked to nursing homes also die at a higher rate than the general population. The median case fatality rate – the number or deaths divided by the number of cases – at facilities with reliable data is 17 percent, significantly higher than the 5 percent fatality rate nationwide.

New York State was only one of several states, though, which enacted orders increasing the virus death tolls.

States that issued orders similar to Cuomo’s recorded comparably grim outcomes. Michigan lost 5% of roughly 38,000 nursing home residents to COVID-19 since the outbreak began. New Jersey lost 12% of its more than 43,000 residents. In Florida, where such transfers were barred, just 1.6% of 73,000 nursing home residents died of the virus. California, after initially moving toward a policy like New York’s, quickly revised it. So far, it has lost 2% of its 103,000 nursing home residents.

And keep in mind that this 43% average is massively dragged down because five states had zero deaths in nursing homes while other states had as many of 80% of their deaths in nursing homes.

This development is magnified in its awfulness upon close inspection of the document which informed the lockdown policies. The second-to-last paragraph in the original 2006 Nature article — the blueprint for the lockdowns, entitled “Strategies for Mitigating an Influenza Pandemic” reads,

Lack of data prevent us from reliably modeling transmission in the important context of residential institutions (for example, care homes, prisons) and health care settings; detailed planning for use of antivirals, vaccines, and infection control measures in such settings are needed, however. We do not present projections of the likely impact of personal protective measures (for example, face masks) on transmission, again due to a lack of data on effectiveness.

The apparent omission of considerations regarding individuals in long-term care facilities by epidemiologists and policymakers, and the consequently disproportionate number of total fatalities among that same population, provides context for a series of hasty, surreptitious actions by politicians to duck accountability (and harvest more power).

It thus becomes increasingly clear that despite driving the U.S. economy into an artificial depression, destroying tens of thousands of businesses and the lives of millions of citizens, and elevating rates of domestic violence, divorce, substance abuse, and suicide, US government policies failed to protect the most vulnerable segment of the population: individuals in nursing homes and other long-term care facilities.

And furthermore, that despite 14 years between the publication of the “Strategies” paper and its real-world implementation, apparently no research was conducted that would have extended its conclusions to those particularly at-risk populations.

This, of course, is a vastly more fundamental issue than the inability of even the most complex computational methods to incorporate and account for social science phenomena. The susceptibility of the elderly and institutionalized, and in particular those with pre-existing conditions, was a ubiquitous consideration of virtually all medical protocols. Yet somehow between the 1970s and today, human knowledge regarding disease prevention and control — a product of informal institutions and cultural mores — was lost or forgotten; and into the vacuum swept the rigidities of top-down edicts informed by scientism: technocrats wielding agent-based models.

Americans expect government agencies to lie and their prognoses and diagnoses to fail. Policy failures are vastly more common than successes, and successes — where they may be found — are always and everywhere a veritable font of unintended consequences.

Far from producing better responses, models and simulations used as detailed outlines (rather than for high-level, mostly abstract insights) amplify, rather than attenuate, the failures of central planning. The model-driven response to the coronavirus pandemic, which now includes directly sacrificing the most vulnerable segment of the population to the virus, is only the latest. And it joins a growing heap of episodes which include the Fed’s response to the late 1920s financial boom and more recently the destruction of Iraq over WMDs that scarcely existed and the botched emergency response to Hurricane Katrina.

Why do we continue to listen?

________________________